What Are NAD+ Precursors?

Key Takeaways

- NAD+ is an essential coenzyme that supports cellular energy production, repair, and defense.

- The body produces NAD+ primarily in the cell cytosol from smaller building blocks called NAD+ precursors—mainly niacin, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside (NR).

- Each NAD+ precursor follows a distinct metabolic route—nicotinamide via the salvage pathway, nicotinic acid via the Preiss–Handler pathway, and NR via the NRK pathway—which affects how efficiently and sustainably each raises NAD+ levels.

- NR is the most efficient and well-tolerated vitamin B3 form, providing a direct, energy-saving route to NAD+ without the side effects of niacin or the enzyme inhibition linked to nicotinamide.

- Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) also contributes to NAD+ production, but must first convert into NR before it can enter cells and be converted into NAD+.

- Because each NAD+ precursor follows a different metabolic pathway, they do not all support cellular health and energy with the same efficiency.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is an essential coenzyme required by every living cell in the body to support cellular energy production, as well as cellular repair and defense processes. Because NAD+ is constantly consumed and recycled within the body, and can naturally decline with age, cells rely on a steady supply of building blocks called NAD+ precursors to maintain NAD+ levels.

A “precursor” is a smaller molecule that cells convert through a series of chemical reactions into a larger, more complex compound—in this case, NAD+. Dietary NAD+ precursors, including forms of vitamin B3, such as niacin (nicotinic acid), nicotinamide (niacinamide), nicotinamide riboside, and, to a lesser degree, tryptophan, are the building blocks that cells use to create more NAD+. Each enters NAD+ metabolism through distinct routes that determine how efficiently they can raise NAD+ levels.

Established NAD+ Precursors

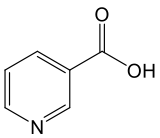

Nicotinic Acid/Niacin (NA)

Niacin, also known as nicotinic acid, is one of the earliest discovered forms of vitamin B3. Discovered in the late 1930s, it quickly gained recognition for its remarkable ability to both prevent and treat pellagra—a severe disease resulting from vitamin B3 deficiency. During the early 1900s, pellagra was widespread across the southern United States, where poverty and corn-based diets were common.¹ʹ² The condition is characterized by the “three Ds”: dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia. If left untreated, it can ultimately lead to death.³

Niacin occurs naturally in a wide range of foods. Good dietary sources include meat (especially liver), poultry, fish, milk, eggs, yeast, legumes, green vegetables, and cereal grains.⁴ The recommended daily allowance (RDA) for niacin equivalents (NE) is 14 mg per day for women and 16 mg per day for men. One milligram of NE is equivalent to either 1 mg of niacin or 60 mg of tryptophan. These intake levels were originally set to prevent pellagra and to ensure adequate vitamin B3 status in the general population.⁵

Beyond its essential nutritional role, niacin has a long history of use for cardiovascular health and is one of the most widely recognized vitamins used to help manage elevated cholesterol.⁶ When combined with statins, niacin has been shown to increase levels of “good” high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol,⁷ while producing a more modest reduction in “bad” low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.⁸

However, niacin supplementation is not without side effects. One of the most common and uncomfortable reactions is flushing—a temporary sensation of warmth, redness, and tingling of the skin caused by dilation of blood vessels.⁹ Although harmless, this reaction often discourages consistent use. To mitigate this, extended-release niacin formulations were developed, which can lessen flushing in some individuals.⁹ Nevertheless, prolonged use of high-dose extended-release niacin has been linked to liver toxicity,⁵ underscoring the need for careful medical supervision during therapeutic use.

At the cellular level, niacin contributes to the synthesis of NAD+ through the Preiss-Handler pathway.¹⁰ In this three-step process, niacin is first converted to nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NaMN), then to nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (NaAD), and finally to NAD+. Although this pathway efficiently produces NAD+ from niacin, it is more energy-intensive than other routes because it involves multiple enzymatic steps that consume ATP (the cell’s primary energy currency) to drive the reactions.

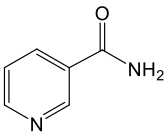

Nicotinamide/Niacinamide (NAM)

Nicotinamide, also known as niacinamide, is another form of vitamin B3 that was identified in the late 1930s, around the same time as niacin (nicotinic acid). Soon after its discovery, nicotinamide became the preferred form of vitamin B3 for nutritional

supplementation and food fortification.¹ Its popularity largely stems from the fact that it does not cause the flushing reaction commonly associated with niacin intake.¹¹

Although nicotinamide is generally better tolerated and more widely used, its biological effects differ from those of niacin in important ways. At high doses, nicotinamide has been shown to inhibit sirtuins—a family of NAD-dependent enzymes that play crucial roles in cellular metabolism, DNA repair, and stress response.¹² Sirtuins are important

NAD-dependent enzymes critical in cellular metabolism and cellular repair processes, overall helping to maintain and regulate cellular homeostasis.¹³ Consequently, excessive nicotinamide intake may theoretically offset some of the potential longevity benefits associated with elevated NAD+ levels.

From a metabolic standpoint, nicotinamide supports NAD+ synthesis primarily through the salvage pathway, a highly efficient two-step process that recycles nicotinamide back into NAD+.¹⁰ This pathway serves as the human body’s main mechanism for maintaining intracellular NAD+ pools, ensuring a steady supply of this essential coenzyme for energy metabolism, cellular repair, and numerous enzymatic reactions.

Nicotinamide Riboside (NR)

Nicotinamide riboside (NR) is the third and most recently identified form of vitamin B3, first discovered in the 1940s. Its biological importance, however, was not fully recognized until 2004, when researchers demonstrated that NR could effectively elevate intracellular levels of NAD+.¹⁴ The same research group also detected trace amounts of NR in milk, establishing it as a naturally occurring nutrient.¹⁴ However, the amount is extremely low: one would need to drink roughly 87 gallons of milk to obtain the same 300 mg dose of NR typically used in supplements.

Although NR belongs to the vitamin B3 family, it exhibits unique metabolic and physiological properties that distinguish it from both niacin and nicotinamide. Unlike niacin, NR does not cause flushing, even at high doses, and unlike nicotinamide, it does not inhibit sirtuin activity.¹⁵ Sirtuins are a family of NAD-dependent enzymes crucial for DNA repair, metabolic regulation, and longevity. In fact, preclinical studies suggest that NR may enhance sirtuin function,¹⁵ supporting cellular health. The specific advantages of NR are explored further in the section below titled “Why Nicotinamide Riboside Stands Apart from Niacin and Nicotinamide.”

At the cellular level, NR supports NAD+ production through the nicotinamide

riboside kinase (NRK) pathway.¹⁴ Once inside the cell, NR is converted in two steps—first into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), and then into NAD+. This pathway bypasses the rate-limiting steps of other NAD+ biosynthetic routes, making NR one of the most direct and metabolically efficient precursors for restoring intracellular NAD+ levels.

Nicotinamide Riboside Salt Forms

To improve stability and bioavailability, NR is commonly formulated as a crystalline salt.¹⁶ Two of the most well-characterized forms are nicotinamide riboside chloride (NRCl) and nicotinamide riboside hydrogen malate (NRHM, or also known as nicotinamide riboside malate). Both deliver the same active NR molecule upon ingestion, which is subsequently converted into NAD+ within cells. However, because the two salts have different molecular weights, with NRHM being heavier, the actual amount of NR delivered per dose varies. For example, a 300 mg dose of NRCl provides roughly 263 mg of NR (the remainder being chloride), whereas the same 300 mg of NRHM provides only about 197 mg of NR, with the rest being hydrogen malate.

Nicotinamide riboside chloride was the first NR salt form to be successfully reviewed twice under the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) New Dietary Ingredient (NDI) notification program (NDI 882; NDI 1062) and successfully notified to the FDA as generally

recognized as safe (GRAS).

Nicotinamide riboside hydrogen malate,¹⁷ a newer salt form, has likewise been successfully notified under the NDI program (NDI 1243) and may offer enhanced stability. However, it has not yet been evaluated as a standalone ingredient in published clinical studies. To date, only one clinical study, published as a preprint, has investigated NRHM in combination with other compounds—such as magnesium beta-hydroxybutyrate, glutathione, and coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10)—to assess potential effects on brain function.¹⁸ As a result, its independent safety and efficacy in humans remain undetermined.

A third option, nicotinamide riboside hydrogen tartrate (NRHT)—also referred to as NR tartrate—represents another recently introduced salt form.¹⁷ Unlike NRCl and NRHM, NR tartrate has been described primarily in technical and production-oriented literature,¹⁷ and no human clinical studies have evaluated its safety, bioavailability, or efficacy. It also lacks any known NDI notifications or GRAS submissions, and no regulatory reviews specific to NR tartrate are publicly accessible. Because of this, there is currently no evidence that NR tartrate is a safe or effective way to raise NAD+ levels in humans. Its higher molecular weight also means that a 300 mg dose delivers even less NR than NRHM—approximately 189 mg—with the rest consisting of hydrogen tartrate.

For a brief comparison of all NR salt forms, see Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of Nicotinamide Riboside Salt Forms

| Salt Form | Dose (for comparative purposes) | NR Content | Regulatory Status in United States | Published Toxicology Studies | Published Human Clinical Evidence |

|

Nicotinamide Riboside Chloride (NRCl; also known as NR Chloride) |

300 mg | 263 mg | Conze et al., 2016 | More than 40 published clinical studies | |

|

Nicotinamide Riboside Hydrogen Malate (NRHM; also known as Nicotinamide Riboside Malate) |

300 mg | 197 mg | NDI 1243 | Dziwenka et al., 2022 | Only one preprint clinical study in combination with other compounds; no standalone NRHM studies |

|

Nicotinamide Riboside Hydrogen Tartrate (NRHT; also known as Nicotinamide Riboside Tartrate) |

300 mg | 189 mg | None | None | No published clinical studies |

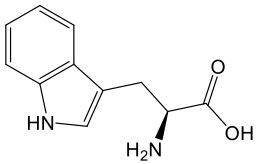

Tryptophan (TRYP)

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid, meaning it must be obtained through the diet since the body cannot synthesize it on its own. It is found abundantly in protein-rich foods such as eggs, meat, poultry, dairy products, and seeds. Once consumed, tryptophan plays several vital roles in human metabolism. It serves as a building block for new proteins, a precursor for serotonin, an important neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation, and for melatonin, the hormone that regulates sleep cycles.¹⁹

Beyond these functions, tryptophan can also serve as a precursor for NAD+ through the de novo biosynthetic pathway. This process involves a sequence of seven enzymatic steps that convert tryptophan into intermediates such as kynurenine and quinolinic acid before ultimately forming NAD+. However, because tryptophan is utilized in numerous other metabolic pathways, only a small fraction of dietary tryptophan is directed toward NAD+ synthesis.²⁰

Calculations estimating “niacin equivalents” suggest that approximately 60 mg of tryptophan can generate the same NAD-raising effect as 1 mg of niacin, although this ratio may vary depending on an individual’s nutritional and metabolic status.²¹

Tryptophan can also be converted into niacin within the body, but this conversion is metabolically inefficient and requires multiple enzymatic reactions.¹ As a result, while tryptophan does contribute to NAD+ biosynthesis, direct intake of vitamin B3 remains a more efficient and reliable way to support and maintain NAD+ levels.

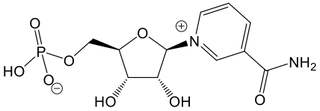

Nicotinamide Mononucleotide (NMN)

Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) is not a form of vitamin B3, but rather an intermediate molecule formed during the conversion of nicotinamide and NR into NAD+.²⁰ʹ²² NMN belongs to a class of molecules called nucleotides, which share structural similarities with the building blocks of DNA.

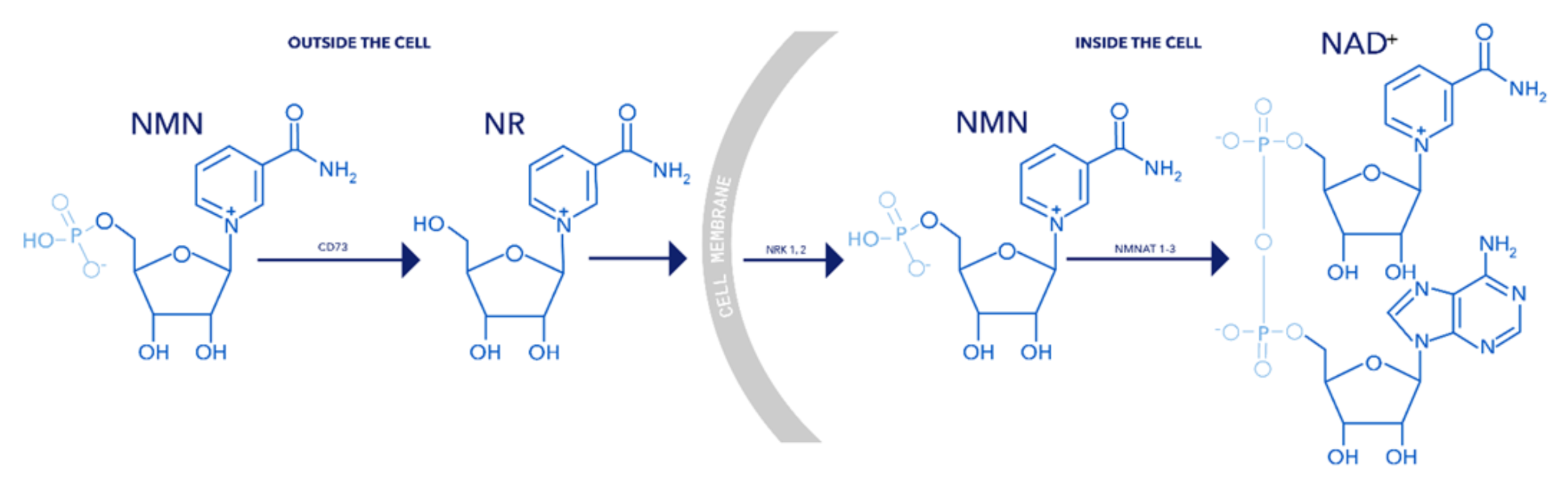

Due to its nucleotide structure and the additional phosphate group, NMN is a larger molecule that cannot easily cross cell membranes on its own. Research suggests that NMN consumed through food or supplements is first converted extracellularly into NR before entering cells.¹⁰ʹ²⁰ʹ²³ʹ²⁴ Once inside, NR is then reconverted back into NMN and subsequently transformed into NAD+, completing the biosynthetic pathway.

In 2022, the U.S FDA ruled that NMN could not be marketed as a dietary supplement because it had previously been investigated as a potential pharmaceutical ingredient. However, in September of 2025, the FDA reversed this decision—officially reinstating NMN as an allowable dietary supplement ingredient. While this reversal has reduced regulatory uncertainty, it also underscores ongoing challenges surrounding product quality, safety, and compliance for the ingredients use in supplements. Even during the exclusion period, NMN supplements continued to appear on the market, often

with questionable purity or unverified sourcing. Furthermore, despite the FDA’s updated position, NMN products may still infringe upon existing patents, posing potential legal risks for manufacturers and brands entering the market.

Read more about the FDA’s reversal of the NMN decision.

Dihydronicotinamide Riboside (NRH)

Dihydronicotinamide riboside (NRH) is a reduced form of NR and was recently identified in 2019 as a novel NAD+ precursor. Unlike NR, which utilizes the traditional NRK pathway, NRH follows a distinct metabolic route.²⁵ After entering the cell, NRH is first converted into dihydronicotinamide mononucleotide (NMNH), which is then oxidized to NADH and ultimately to NAD+.

Early preclinical studies suggest that NRH can raise NAD+ levels more rapidly and efficiently than NR, indicating a potentially powerful pathway for enhancing cellular energy metabolism.²⁶ However, NRH is chemically unstable and prone to degradation, which may limit its practical application.²⁷ To date, no human studies have been conducted to assess its safety, bioavailability, or long-term effects.

While the recent discovery of NRH opened an exciting new direction in NAD+ research, it remains an experimental compound that requires further investigation before it can be considered a viable option for human supplementation.

Nicotinic Acid Riboside (NaR)

Nicotinic acid riboside (NaR) is a lesser-known member of the vitamin B3 family and a structural relative of NR. It was first identified in 2007 as a novel NAD+ metabolite and precursor.²⁸ Unlike NR, which is converted to NAD+ through the NRK pathway, NaR follows the Preiss-Handler pathway—the same route utilized by niacin.²⁸ Within cells, NaR is first converted into nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NaMN) and subsequently converted into NAD+.

Although research on NaR remains limited, early preclinical studies in cell and animal models suggest that it can act as an effective NAD+ precursor.²⁹ Evidence also indicates that NaR may exhibit more tissue-specific activity than NR, suggesting it could have selective effects in specific organs or cell types.³⁰

Different Pathways to the Same Goal: NAD+ Production

Not All Vitamin B3s Take the Same Route

Although niacin, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside all belong to the vitamin B3 family, each is structurally distinct and therefore processed differently by the body. These differences influence not only how each molecule is metabolized but also its relative safety, efficacy, and ability to support various aspects of health.

The goal of NAD+ production within cells is simple: maximize energy output. Yet, the very processes that generate energy also consume energy, making efficiency crucial. NAD+ is a key molecule in this process, converting nutrients into usable energy. Because cells must continuously synthesize NAD+ to sustain metabolism, the efficiency of NAD+ production can directly affect overall energy availability.

Most cellular NAD+ is synthesized from three primary building blocks, all derived from vitamin B3: niacin, nicotinamide, and NR. While each can increase NAD+ levels, the pathways they follow differ in complexity and efficiency, determining how effectively they support energy metabolism.

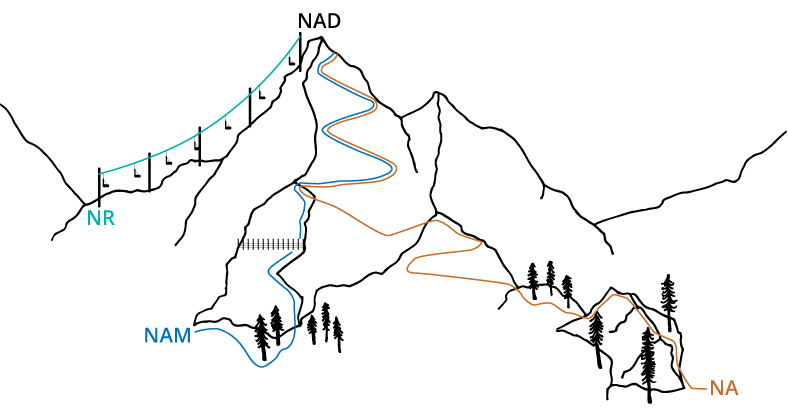

Imagine three different routes to the same mountaintop, representing NAD+ production (Figure 1). Niacin and nicotinamide reach the summit, but their trails are longer and more winding, with nicotinamide facing additional obstacles that slow progress. These detours reflect the extra steps and energy (ATP) required to convert these forms into NAD+.³¹ In contrast, NR takes a more direct route—like a ski lift to the top. This streamlined pathway conserves both energy and cellular resources, allowing more efficient NAD+ production.

Figure 1. Simplified illustration of vitamin B3 pathways leading to NAD+. Although all routes ultimately reach the same endpoint, some require more cellular effort than others. For instance, niacin’s pathway is depicted as longer to reflect the extra energy and enzymatic steps needed to convert it into NAD+.

Why Nicotinamide Riboside Stands Apart from Niacin and Nicotinamide

Among the vitamin B3 family, NR exhibits distinct metabolic and physiological advantages that set it apart from both niacin and nicotinamide. These advantages explain its more direct and energy-efficient route to NAD+ production.

Unlike niacin, NR does not activate the GPR109A receptor, which causes the uncomfortable flushing commonly seen with high-dose niacin supplementation.³² Clinical studies have consistently shown that NR supplementation is well-tolerated and does not cause flushing—even at doses up to 3,000 mg per day.³³⁻³⁵

NR also differs from nicotinamide in that it does not inhibit sirtuins; rather, it has been shown to support their activity. A preclinical study published in Nature Communications directly compared niacin, nicotinamide, and NR under identical experimental conditions and found that NR was the most effective at increasing NAD+ levels and enhancing sirtuin activity among the three.¹⁵

Mechanistic Advantages of Nicotinamide Riboside

NR follows a simple, more energy-efficient route than niacin and nicotinamide.³¹ Once inside the cell, it is converted to NAD+ in just two steps through the NRK pathway.³⁶ This pathway bypasses NAMPT, the rate-limiting enzyme in the nicotinamide salvage pathway, which is known to decline with age in both mice and humans.³⁷ By sidestepping this bottleneck, NR maintains NAD+ regeneration even when NAMPT activity is reduced.

Beyond Increasing NAD+: Broader Benefits of NR

Beyond its efficiency in NAD+ synthesis, NR provides several unique biological advantages compared to nicotinamide:

- Metabolic stress resilience: Mice lacking NRK activity (and therefore unable to convert NR to NAD+) were more susceptible to metabolic stress and developed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Nicotinamide supplementation could not fully compensate for the loss of NR utilization.³⁸

- Cardiovascular and stem cell benefits: In mouse models, NR supplementation improved heart function and enhanced hematopoietic stem cell expansion—benefits not observed with nicotinamide.³⁹⁻⁴¹

- Viral infection response: During SARS-CoV-2 infection, NAD+ levels declined sharply in cells, ferrets, and human lung tissue. Gene expression analysis showed that infected cells preferentially activated NR-utilizing pathways to restore NAD+ levels. Similarly, in a Zika virus mouse model, NR supplementation replenished NAD+, improved survival, and reduced brain damage—effects that nicotinamide could not replicate. Remarkably, the NMRK2 gene (encoding the NRK enzyme) increased approximately 150-fold during infection, while NAMPT rose only twofold.⁴²ʹ⁴³

Collectively, these findings highlight NR as a uniquely effective and versatile NAD+ precursor, fueling growing scientific and clinical interest in its potential applications across health and healthy aging.

NR vs NMN: Which NAD+ Precursor Works Better?

While both NR and NMN are NAD+ precursors, the difference between the two comes down to biochemical efficiency. The primary distinction between the two lies in their chemical structures. NR, being a simpler molecule, can directly enter cells and is readily converted into NAD+.

In contrast, NMN has an additional phosphate group, which requires an additional conversion step outside the cell before it can be utilized. Specifically, NMN must first be converted to NR before it can enter the cell (Figure 1). This additional step introduces inefficiencies, ultimately reducing the overall effectiveness of NMN supplementation.

Although one mouse study proposed an NMN-specific transporter (Slc12a8), these findings have not been replicated in humans.⁴⁴ Multiple independent studies confirm that NMN cannot efficiently cross the cell membrane and must first be converted to NR.⁴⁵⁻⁴⁷ In contrast, NR can directly enter human cells via a family of transport proteins called equilibrative nucleoside transporters.³⁶

Figure 2. Chemical structures and biosynthetic pathway of NR, NMN, and NAD+. Outside the cell, NMN must first be converted into NR to enter the cell. Once inside, NR can be reconverted to NMN and then further metabolized into NAD+.

Head-to-head research further underscores NR’s superior performance. In one preclinical study, equal 500 mg doses of NR and NMN increased liver NAD+ levels by 220% and 170%, respectively—making NR roughly 23% more efficient at increasing NAD+ levels.²³

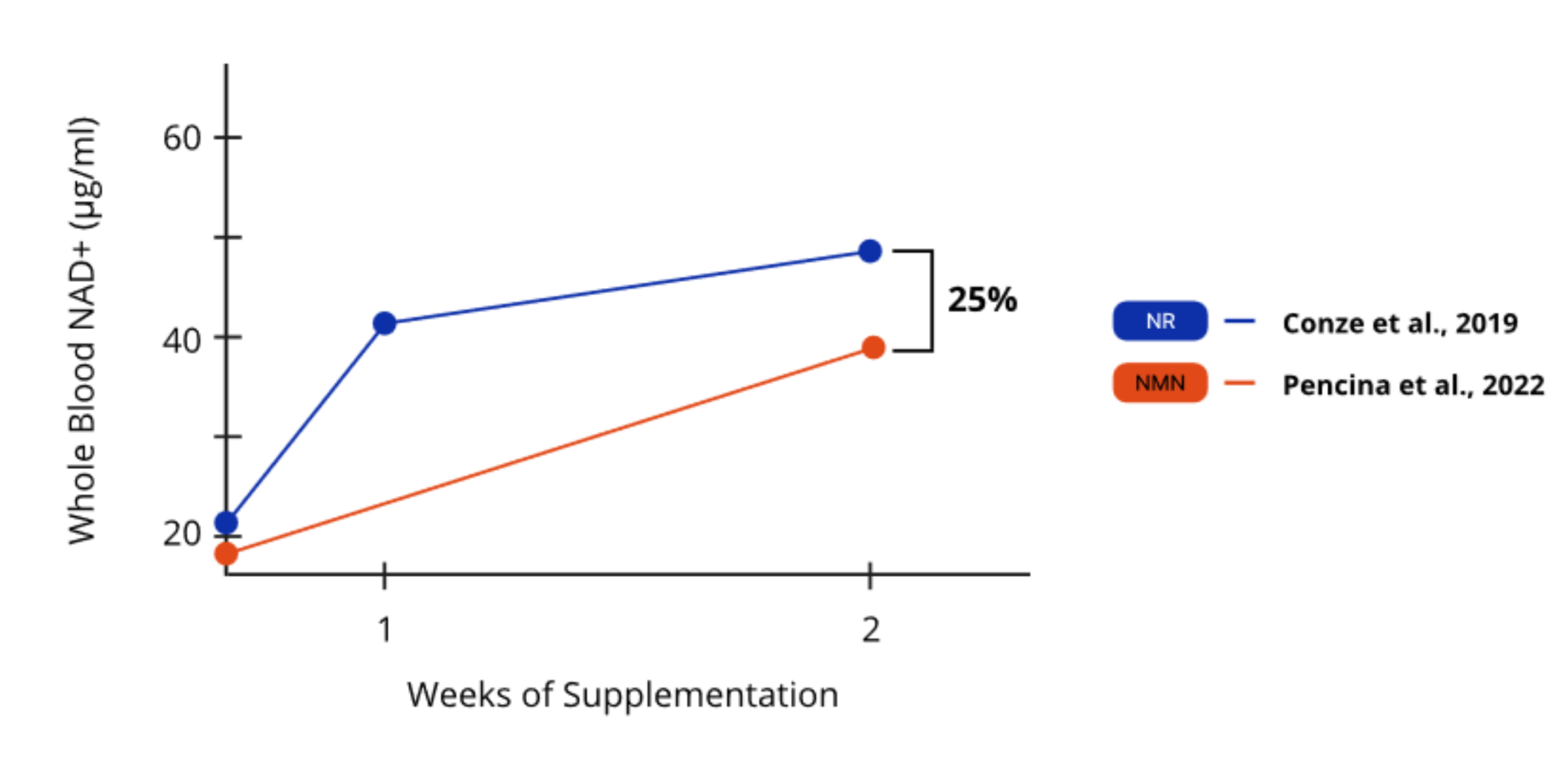

Clinical studies also support NR’s greater effectiveness. In two separate trials involving healthy middle-aged to older adults,³³ʹ⁴⁸ participants who received 1,000 mg of NR experienced a 25% greater increase in whole blood NAD+ levels after just two weeks of supplementation compared to those who received NMN. This demonstrates that NR was 25% more effective at raising whole blood NAD+ levels over the two-week period (Figure 2).

Figure 3. NR was 25% more effective at raising whole blood NAD+ levels after two weeks.

Beyond NAD+ synthesis, NR offers a unique dual benefit: it not only fuels NAD+ production but also inhibits CD38, an enzyme that degrades NAD+ and becomes increasingly more active with age.⁴⁹ By inhibiting CD38, NR not only increases NAD+ production but also helps preserve it, effectively counteracting the age-related decline in NAD+ levels.⁵⁰ In contrast, NMN only contributes to NAD+ synthesis and does not inhibit CD38, making NR particularly advantageous for supporting cellular energy and resilience during aging.

Conclusion: The Cellular Pathways That Power Life

Every living cell depends on a steady supply of NAD+ to generate energy, repair damage, and respond to stress. The body can produce NAD+ from several precursors—niacin, nicotinamide, NR, NMN, and tryptophan—each following a distinct biochemical route.

Niacin and nicotinamide rely on longer, energy-intensive pathways, and nicotinamide can also inhibit certain NAD-dependent enzymes. Tryptophan contributes through the de novo pathway but only modestly, while NMN converts to NR before entering cells. NR provides the most direct and efficient route, helping maintain NAD+ levels even under metabolic or age-related stress.

Taken together, these pathways show that while multiple nutrients can support NAD+ metabolism, the efficiency and overall impact on cellular health depend on which precursor and pathway the body uses. Understanding these differences can help clarify why some strategies for increasing NAD+ may be more effective than others.

References

1. Higdon, J., Drake, V. J., Delage, B., & Meyer-Ficca, M. (2018). Niacin. https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/vitamins/niacin

2. Meyer-Ficca, M., & Kirkland, J. B. (2016). Niacin. Advances in Nutrition, 7(3), 556–558. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.115.011239

3. Hegyi, J., Schwartz, R. A., & Hegyi, V. (2004). Pellagra: Dermatitis, dementia, and diarrhea. International Journal of Dermatology, 43(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01959.x

4. (NDA), E. P. on D. P. N. and A. (2014). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for niacin. EFSA Journal, 12(7), 3759. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2014.3759

5. Supplements, N. O. of D. (2022, November 18). Niacin - Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Niacin-HealthProfessional/

6. Song, W.-L., & FitzGerald, G. A. (2013). Niacin, an old drug with a new twist. Journal of Lipid Research, 54(10), 2586–2594. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.r040592

7. Villines, T. C., Kim, A. S., Gore, R. S., & Taylor, A. J. (2012). Niacin: The Evidence, Clinical Use, and Future Directions. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 14(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-011-0212-1

8. Ratini, M. (2020). Niacin (Vitamin B3) : Benefits, Dosage, Sources, Risks. https://www.webmd.com/diet/supplement-guide-niacin#1

9. Kamanna, V. S., Ganji, S. H., & Kashyap, M. L. (2009). The mechanism and mitigation of niacin-induced flushing. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 63(9), 1369–1377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02099.x

10. Fang, E. F., Lautrup, S., Hou, Y., Demarest, T. G., Croteau, D. L., Mattson, M. P., & Bohr, V. A. (2017). NAD+ in Aging: Molecular Mechanisms and Translational Implications. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 23(10), 899–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2017.08.001

11. MacKay, D., Hathcock, J., & Guarneri, E. (2012). Niacin: chemical forms, bioavailability, and health effects. Nutrition Reviews, 70(6), 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00479.x

12. Hwang, E. S., & Song, S. B. (2020). Possible Adverse Effects of High-Dose Nicotinamide: Mechanisms and Safety Assessment. Biomolecules, 10(5), 687. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10050687

13. Kupis, W., Pałyga, J., Tomal, E., & Niewiadomska, E. (2016). The role of sirtuins in cellular homeostasis. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry, 72(3), 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13105-016-0492-6

14. Bieganowski, P., & Brenner, C. (2004). Discoveries of Nicotinamide Riboside as a Nutrient and Conserved NRK Genes Establish a Preiss-Handler Independent Route to NAD+ in Fungi and Humans. Cell, 117(4), 495–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00416-7

15. Trammell, S. A. J., Schmidt, M. S., Weidemann, B. J., Redpath, P., Jaksch, F., Dellinger, R. W., Li, Z., Abel, E. D., Migaud, M. E., & Brenner, C. (2016). Nicotinamide riboside is uniquely and orally bioavailable in mice and humans. Nature Communications, 7(1), 12948. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12948

16. Jain, R., & Tiwari, A. (2024). Nicotinamide Riboside: An Update. Matrix Science Pharma, 8(3), 62–64. https://doi.org/10.4103/mtsp.mtsp_10_24_1

17. Schabert, G., Haase, R., Parris, J., Pala, L., Hery-Barranco, A., Spingler, B., & Spitz, U. (2021). New Crystalline Salts of Nicotinamide Riboside as Food Additives. Molecules, 26(9), 2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26092729

18. Breuer, L. T., Fickling, S. D., Krause, D. A., D’Arcy, R. C. N., Frizzell, T. O., Gendron, T., & Stuart, M. J. (2023). The effects of a dietary supplement on brain function and structure in Junior A ice hockey players: a prospective randomized trial. medRxiv, 2023.04.03.23288079. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.03.23288079

19. Höglund, E., Øverli, Ø., & Winberg, S. (2019). Tryptophan Metabolic Pathways and Brain Serotonergic Activity: A Comparative Review. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10, 158. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00158

20. Cantó, C., Menzies, K. J., & Auwerx, J. (2015). NAD+ Metabolism and the Control of Energy Homeostasis: A Balancing Act between Mitochondria and the Nucleus. Cell Metabolism, 22(1), 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.023

21. Bogan, K. L., & Brenner, C. (2008). Nicotinic Acid, Nicotinamide, and Nicotinamide Riboside: A Molecular Evaluation of NAD+ Precursor Vitamins in Human Nutrition. Annual Review of Nutrition, 28(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155443

22. Garrido, A., & Djouder, N. (2017). NAD+ Deficits in Age-Related Diseases and Cancer. Trends in Cancer, 3(8), 593–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2017.06.001

23. Ratajczak, J., Joffraud, M., Trammell, S. A. J., Ras, R., Canela, N., Boutant, M., Kulkarni, S. S., Rodrigues, M., Redpath, P., Migaud, M. E., Auwerx, J., Yanes, O., Brenner, C., & Cantó, C. (2016). NRK1 controls nicotinamide mononucleotide and nicotinamide riboside metabolism in mammalian cells. Nature Communications, 7(1), 13103. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13103

24. Grozio, A., Sociali, G., Sturla, L., Caffa, I., Soncini, D., Salis, A., Raffaelli, N., Flora, A. D., Nencioni, A., & Bruzzone, S. (2013). CD73 Protein as a Source of Extracellular Precursors for Sustained NAD+ Biosynthesis in FK866-treated Tumor Cells*. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288(36), 25938–25949. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m113.470435

25. Yang, Y., Zhang, N., Zhang, G., & Sauve, A. A. (2020). NRH salvage and conversion to NAD+ requires NRH kinase activity by adenosine kinase. Nature Metabolism, 2(4), 364–379. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-020-0194-9

26. Yang, Y., Mohammed, F. S., Zhang, N., & Sauve, A. A. (2019). Dihydronicotinamide riboside is a potent NAD+ concentration enhancer in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 294(23), 9295–9307. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.ra118.005772

27. Zarei, A., Khazdooz, L., Enayati, M., Madarshahian, S., Wooster, T. J., Ufheil, G., & Abbaspourrad, A. (2021). Dihydronicotinamide riboside: synthesis from nicotinamide riboside chloride, purification and stability studies. RSC Advances, 11(34), 21036–21047. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1ra02062e

28. Tempel, W., Rabeh, W. M., Bogan, K. L., Belenky, P., Wojcik, M., Seidle, H. F., Nedyalkova, L., Yang, T., Sauve, A. A., Park, H.-W., & Brenner, C. (2007). Nicotinamide Riboside Kinase Structures Reveal New Pathways to NAD+. PLoS Biology, 5(10), e263. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0050263

29. Song, W.-S., Shen, X., Du, K., Ramirez, C. B., Park, S. H., Cao, Y., Le, J., Bae, H., Kim, J., Chun, Y., Khong, N. J., Kim, M., Jung, S., Choi, W., Lopez, M. L., Said, Z., Song, Z., Lee, S.-G., Nicholas, D., … Yang, Q. (2025). Nicotinic acid riboside maintains NAD+ homeostasis and ameliorates aging-associated NAD+ decline. Cell Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2025.04.007

30. Tempel, W., Rabeh, W. M., Bogan, K. L., Belenky, P., Wojcik, M., Seidle, H. F., Nedyalkova, L., Yang, T., Sauve, A. A., Park, H.-W., & Brenner, C. (2007). Nicotinamide Riboside Kinase Structures Reveal New Pathways to NAD+. PLoS Biology, 5(10), e263. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0050263

31. She, J., Sheng, R., & Qin, Z.-H. (2021). Pharmacology and Potential Implications of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Precursors. Aging and Disease, 12(8), 1879–1897. https://doi.org/10.14336/ad.2021.0523

32. Benyó, Z., Gille, A., Kero, J., Csiky, M., Suchánková, M. C., Nüsing, R. M., Moers, A., Pfeffer, K., & Offermanns, S. (2005). GPR109A (PUMA-G/HM74A) mediates nicotinic acid–induced flushing. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 115(12), 3634–3640. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci23626

33. Conze, D., Brenner, C., & Kruger, C. L. (2019). Safety and Metabolism of Long-term Administration of NIAGEN (Nicotinamide Riboside Chloride) in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial of Healthy Overweight Adults. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 9772. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46120-z

34. Dollerup, O. L., Christensen, B., Svart, M., Schmidt, M. S., Sulek, K., Ringgaard, S., Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H., Møller, N., Brenner, C., Treebak, J. T., & Jessen, N. (2018). A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of nicotinamide riboside in obese men: safety, insulin-sensitivity, and lipid-mobilizing effects. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 108(2), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy132

35. Berven, H., Kverneng, S., Sheard, E., Søgnen, M., Geijerstam, S. A. A., Haugarvoll, K., Skeie, G.-O., Dölle, C., & Tzoulis, C. (2023). NR-SAFE: a randomized, double-blind safety trial of high dose nicotinamide riboside in Parkinson’s disease. Nature Communications, 14(1), 7793. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43514-6

36. Kropotov, A., Kulikova, V., Nerinovski, K., Yakimov, A., Svetlova, M., Solovjeva, L., Sudnitsyna, J., Migaud, M. E., Khodorkovskiy, M., Ziegler, M., & Nikiforov, A. (2021). Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporters Mediate the Import of Nicotinamide Riboside and Nicotinic Acid Riboside into Human Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(3), 1391. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031391

37. Guia, R. M. de, Agerholm, M., Nielsen, T. S., Consitt, L. A., Søgaard, D., Helge, J. W., Larsen, S., Brandauer, J., Houmard, J. A., & Treebak, J. T. (2019). Aerobic and resistance exercise training reverses age‐dependent decline in NAD+ salvage capacity in human skeletal muscle. Physiological Reports, 7(12), e14139. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.14139

38. Sambeat, A., Ratajczak, J., Joffraud, M., Sanchez-Garcia, J. L., Giner, M. P., Valsesia, A., Giroud-Gerbetant, J., Valera-Alberni, M., Cercillieux, A., Boutant, M., Kulkarni, S. S., Moco, S., & Canto, C. (2019). Endogenous nicotinamide riboside metabolism protects against diet-induced liver damage. Nature Communications, 10(1), 4291. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12262-x

39. Diguet, N., Trammell, S. A. J., Tannous, C., Deloux, R., Piquereau, J., Mougenot, N., Gouge, A., Gressette, M., Manoury, B., Blanc, J., Breton, M., Decaux, J.-F., Lavery, G. G., Baczkó, I., Zoll, J., Garnier, A., Li, Z., Brenner, C., & Mericskay, M. (2018). Nicotinamide Riboside Preserves Cardiac Function in a Mouse Model of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circulation, 137(21), 2256–2273. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.116.026099

40. Vignier, N., Chatzifrangkeskou, M., Rodriguez, B. M., Mericskay, M., Mougenot, N., Wahbi, K., Bonne, G., & Muchir, A. (2018). Rescue of biosynthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide protects the heart in cardiomyopathy caused by lamin A/C gene mutation. Human Molecular Genetics, 27(22), 3870–3880. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddy278

41. Vannini, N., Campos, V., Girotra, M., Trachsel, V., Rojas-Sutterlin, S., Tratwal, J., Ragusa, S., Stefanidis, E., Ryu, D., Rainer, P. Y., Nikitin, G., Giger, S., Li, T. Y., Semilietof, A., Oggier, A., Yersin, Y., Tauzin, L., Pirinen, E., Cheng, W.-C., … Naveiras, O. (2019). The NAD-Booster Nicotinamide Riboside Potently Stimulates Hematopoiesis through Increased Mitochondrial Clearance. Cell Stem Cell, 24(3), 405-418.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2019.02.012

42. Heer, C. D., Sanderson, D. J., Voth, L. S., Alhammad, Y. M. O., Schmidt, M. S., Trammell, S. A. J., Perlman, S., Cohen, M. S., Fehr, A. R., & Brenner, C. (2020). Coronavirus infection and PARP expression dysregulate the NAD metabolome: An actionable component of innate immunity. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 295(52), 17986–17996. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.ra120.015138

43. Pang, H., Jiang, Y., Li, J., Wang, Y., Nie, M., Xiao, N., Wang, S., Song, Z., Ji, F., Chang, Y., Zheng, Y., Yao, K., Yao, L., Li, S., Li, P., Song, L., Lan, X., Xu, Z., & Hu, Z. (2021). Aberrant NAD+ metabolism underlies Zika virus–induced microcephaly. Nature Metabolism, 3(8), 1109–1124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-021-00437-0

44. Grozio, A., Mills, K. F., Yoshino, J., Bruzzone, S., Sociali, G., Tokizane, K., Lei, H. C., Cunningham, R., Sasaki, Y., Migaud, M. E., & Imai, S. (2019). Slc12a8 is a nicotinamide mononucleotide transporter. Nature Metabolism, 1(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-018-0009-4

45. Fletcher, R. S., Ratajczak, J., Doig, C. L., Oakey, L. A., Callingham, R., Xavier, G. D. S., Garten, A., Elhassan, Y. S., Redpath, P., Migaud, M. E., Philp, A., Brenner, C., Canto, C., & Lavery, G. G. (2017). Nicotinamide riboside kinases display redundancy in mediating nicotinamide mononucleotide and nicotinamide riboside metabolism in skeletal muscle cells. Molecular Metabolism, 6(8), 819–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2017.05.011

46. Nikiforov, A., Dölle, C., Niere, M., & Ziegler, M. (2011). Pathways and Subcellular Compartmentation of NAD Biosynthesis in Human Cells FROM ENTRY OF EXTRACELLULAR PRECURSORS TO MITOCHONDRIAL NAD GENERATION*. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 286(24), 21767–21778. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m110.213298

47. Mateuszuk, Ł., Campagna, R., Kutryb-Zając, B., Kuś, K., Słominska, E. M., Smolenski, R. T., & Chlopicki, S. (2020). Reversal of endothelial dysfunction by nicotinamide mononucleotide via extracellular conversion to nicotinamide riboside. Biochemical Pharmacology, 178(4), 114019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114019

48. Pencina, K. M., Lavu, S., Santos, M. dos, Beleva, Y. M., Cheng, M., Livingston, D., & Bhasin, S. (2022). MIB-626, an Oral Formulation of a Microcrystalline Unique Polymorph of β-Nicotinamide Mononucleotide, Increases Circulating Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide and its Metabolome in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 78(1), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glac049

49. Covarrubias, A. J., Perrone, R., Grozio, A., & Verdin, E. (2021). NAD+ metabolism and its roles in cellular processes during ageing. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 22(2), 119–141. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-020-00313-x

50. Kao, G., Zhang, X.-N., Nasertorabi, F., Katz, B. B., Li, Z., Dai, Z., Zhang, Z., Zhang, L., Louie, S. G., Cherezov, V., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Nicotinamide Riboside and CD38: Covalent Inhibition and Live-Cell Labeling. JACS Au, 4(11), 4345–4360. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.4c00695