Key Takeaways

- NAD+ is a crucial coenzyme involved in cellular energy, metabolism, repair, and signaling.

- First discovered in 1906, NAD+ research has evolved from fermentation studies to modern investigations into aging, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular health.

- Early breakthroughs include the purification of NAD+, the discovery of vitamin precursors like niacin, and the mapping of biosynthesis pathways, such as the Preiss-Handler pathway.

- Modern research explores NAD+ precursors like nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) for increasing NAD+ levels, with clinical studies investigating impacts on brain health, muscle function, and overall wellness.

- Consumer interest in NAD+ supplementation is growing, ranging from intravenous and injectable therapies to oral and liposomal supplements, reflecting its perceived role in supporting long-term health.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is an indispensable coenzyme involved in cellular energy production, metabolism, and repair, as well as cellular signaling and gene regulation.

Over the past century, scientific understanding of NAD+ has progressed from its initial identification as a component of yeast fermentation to its current status as a central molecule in aging biology and metabolic research.

The following historical timeline outlines the major discoveries that shaped contemporary knowledge of NAD+ and its biological significance.

1906 – NAD+ was discovered by Arthur Harden and William John Young.

The formal history of NAD+ begins in 1906 with the pioneering work of Arthur Harden and William John Young, whose research built directly upon the foundation laid by Louis Pasteur a few decades earlier. Pasteur had demonstrated that yeast cells were responsible for fermentation, the process in which yeast cells consume sugars and convert them to alcohol and other products. Fermentation in yeast is the same as one of the metabolic processes that occurs in animals and humans to generate energy (lactic acid fermentation).

In their groundbreaking work, Arthur Harden and William John Young sought to learn more about how yeast perform fermentation.¹ They tried to reproduce the process outside of the yeast cells. Using laboratory techniques, they were able to break open yeast cells and separate their contents into two fractions. They observed that one fraction was heat-sensitive, losing its ability to catalyze fermentation when exposed to elevated temperatures, while another fraction was heat-stable, retaining its activity despite heat treatment.

By separating and then recombining the fractions, Harden and Young were able to show that the fermentation activity of the heat-sensitive fraction depended critically on the presence of the heat-stable one. They surmised that the heat-sensitive fraction contained proteins responsible for fermentation, and the heat-stable fraction contained cofactors and other stable molecules that helped the proteins perform the reactions. Among these was the molecule now known as NAD+.

1929 – Hans von Euler-Chelpin won the Nobel Prize with Arthur Harden for their investigation into fermentation.

Originally a student of art, Hans von Euler-Chelpin shifted his focus to chemistry and continued Harden and Young’s work by studying the details of the reactions that occur in the fermentation process.

In this work, von Euler-Chelpin was able to further separate components of the heat-stable fraction of the yeast cells. In doing so, he purified the NAD+ molecule. von Euler-Chelpin is credited with uncovering the first information about the chemical shape and properties of the cofactor that allowed fermentation reactions to proceed.²

1936 – Otto Heinrich Warburg demonstrated the role of NAD+ in fermentation reactions.

Otto Heinrich Warburg studied the chemical processes of fermentation reactions and discovered that NAD+ is needed for a certain type of chemical reaction, called a hydride transfer. In these reactions, a hydrogen atom along with its electrons is transferred from one molecule to another. These types of reactions are essential to cellular metabolism and many other chemical processes that are required to sustain life.

Warburg’s work showed that, during fermentation, the nicotinamide portion of NAD+ accepts the hydride to become NADH and allows the reaction to proceed.³

1938 – Conrad Elvehjem discovered “anti-black tongue factor,” the first vitamin precursors of NAD+.

In the early 1900s, pellagra was a common disease that caused symptoms such as diarrhea, dermatitis, and dementia. Joseph Goldberger conducted the first studies linking pellagra to a nutritional deficiency. However, some of his human experiments were controversial and ethically problematic, as they involved deliberately inducing the disease in institutionalized individuals by withholding certain nutritious foods from their diets.

Conrad Elvehjem furthered this work by performing controlled experiments in dogs. Elvehem observed that when dogs get pellagra, due to a poor diet, their tongues turn black. This model animal system allowed Elvehjem to give dogs different food extracts and see which ones helped dogs recover from the “black tongue” disease. Through careful purification of the food extracts,⁴ Elvehjem discovered that niacin, also known as nicotinic acid, cured pellagra, or “black tongue” disease, in dogs, establishing it as the first identified vitamin precursor of NAD+.⁵

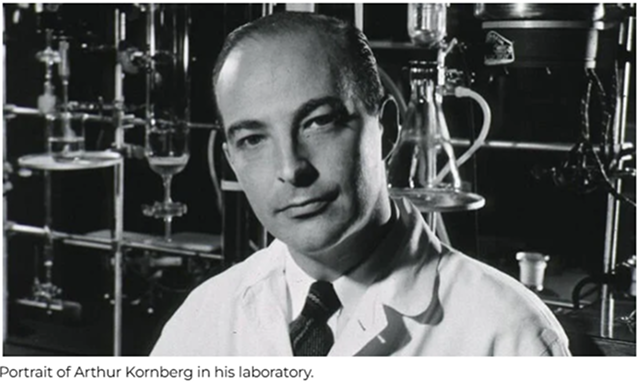

1948 – Arthur Kornberg discovered the first enzyme involved in NAD+ biosynthesis.

After Hans von Euler-Chelpin’s early purification of NAD+ and Conrad Elvehjem’s discovery of niacin as the nutrient that prevented pellagra, Arthur Kornberg studied the way that NAD+ is made in the body.

By this time, methods for the purification of proteins and coenzymes had advanced to the point that scientists could purify all the components they thought would be needed for a reaction. They could then test their theories by combining the purified components and looking for evidence that the reaction had happened.

Kornberg purified the components needed for the NAD-generating reaction from yeast cells and combined them in an experimental setup to demonstrate that they were responsible for creating NAD+. His experiments were the first to demonstrate the chemical reaction cells use to create NAD+ from the precursor molecule nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN).⁶

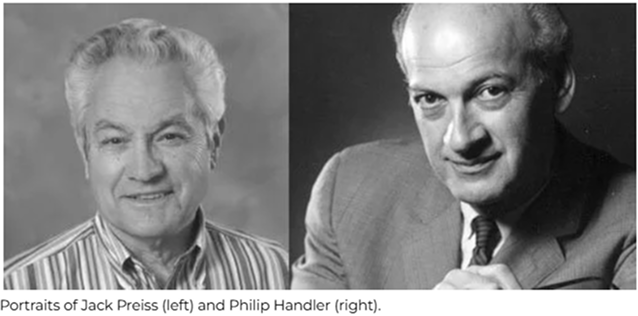

1958 – Jack Preiss and Philip Handler discovered the pathway by which niacin is converted into NAD+.

While Conrad Elvehjem had shown that nicotinic acid prevents pellagra, and Arthur Kornberg had demonstrated how cells synthesize NAD+ from NMN, the connection between niacin and NAD+ production remained unclear.

Jack Preiss and Philip Handler addressed this gap, demonstrating that niacin is converted into NAD+ through a three-step process and identifying the enzymes responsible for each step. This metabolic route is now known as the Preiss-Handler pathway.⁷'⁸

1963 – Mandel and colleagues described the first chemical reaction in which NAD+ is broken down into its component parts.

By this time, researchers had established that NAD+ was essential for fermentation in yeast and for health in humans and animals, and they had elucidated various pathways by which cells synthesize NAD+. However, no studies had yet demonstrated how NAD could be chemically broken down.

Mandel and colleagues identified a reaction in which NAD+ is cleaved into two components: nicotinamide and ADP-ribose.⁹

2000 – Scientists discovered that sirtuin enzymes break the NAD+ molecule into its component parts.

Sirtuin enzymes were first identified in yeast for their remarkable ability to extend lifespan. Biochemical studies investigating how yeast sirtuins influence longevity revealed that these enzymes use NAD+ to regulate gene activity by keeping certain genes “silent” so they cannot function.

To do this, the sirtuin enzymes break NAD+ and use its components to “deacetylate” other proteins in the cell. Deacetylating histone proteins associated with DNA, for example, can change how the cell accesses nearby genes in the DNA.¹⁰

2004 – Charles Brenner and colleagues discovered the pathway by which nicotinamide riboside is converted into NAD+.

Similar to the discoveries of niacin by Conrad Elvehjem and the work of Preiss and Handler, Brenner and colleagues identified a new NAD+ precursor called nicotinamide riboside (NR). They also characterized the enzymes that eukaryotic cells use to convert NR into NAD+.

Their studies uncovered a two-step pathway for this conversion, and follow-up work showed that feeding cells with NR increased NAD+ levels and extended yeast lifespan.¹¹'¹²

2010s – Research on NAD+ accelerated, revealing its central role in aging, metabolism, and disease, and fueling interest in its therapeutic potential.

During the 2010s, research on NAD+ accelerated dramatically, driven by growing evidence that NAD+ levels decline with age.¹³

The decade also saw the emergence of translational research, with clinical studies investigating NAD+ precursors, such as NR and NMN, as potential therapeutics for metabolic, neurodegenerative, and cardiovascular disorders.

Collectively, the 2010s established NAD+ as a central target in age-related health and disease.

2020 to Present Day – Scientists around the world are uncovering new therapeutic benefits of NAD+, revealing its potential to support brain health, cellular function, and combat age-related decline.

Research on NAD+ has entered an exciting new era, with scientists worldwide uncovering its broad therapeutic potential, including applications for neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s¹⁴ and Alzheimer’s disease.¹⁵ Recent studies have expanded our understanding of NAD+ beyond its essential role in cellular energy metabolism, highlighting its significance for brain health,¹⁴ cognition,¹⁶ and heart health.¹⁷

Researchers are actively investigating strategies to boost NAD+, with studies on precursors like NR and NMN appearing almost weekly. Human clinical trials at various stages are shedding light on how NAD+ impacts cardiovascular and neurological health, as well as broader areas such as muscle function and overall wellness.

Reflecting this growing scientific and public interest, NAD+ supplementation is gaining traction in the consumer space, from intravenous therapies and injectables to oral supplements and liposomal formulations, as more people seek evidence-based ways to support long-term health.

References

- Harden, A., & Young, W. J. (1906). The alcoholic ferment of yeast-juice. Part II.—The coferment of yeast-juice. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character, 78(526), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1906.0070

- Euler, H. von. (1930). Fermentation of Sugars and Fermentative Enzymes. Nobel Prize Lecture. https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/euler-chelpin-lecture.pdf

- Warburg, O., & Christian, W. (1936). Pyridin, der wasserstoffübertragende Bestandteil von Gärungsfermenten. Helvetica Chimica Acta, 19(1), E79–E88. https://doi.org/10.1002/hlca.193601901199

- Elvehjem, C. A., Madden, R. J., Strong, F. M., & Woolley, D. W. (1938). THE ISOLATION AND IDENTIFICATION OF THE ANTI-BLACK TONGUE FACTOR. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 123(1), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(18)74164-1

- Axelrod, A. E., Madden, R. J., & Elvehjem, C. A. (1939). THE EFFECT OF A NICOTINIC ACID DEFICIENCY UPON THE COENZYME I CONTENT OF ANIMAL TISSUES. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 131(1), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(18)73482-0

- KORNBERG, A. (1948). The participation of inorganic pyrophosphate in the reversible enzymatic synthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 176(3), 1475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18098602

- PREISS, J., & HANDLER, P. (1958). Biosynthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide. I. Identification of intermediates. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 233(2), 488–492. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13563526

- PREISS, J., & HANDLER, P. (1958). Biosynthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide. II. Enzymatic aspects. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 233(2), 493–500. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13563527

- Chambon, P., Weill, J. D., & Mandel, P. (1963). Nicotinamide mononucleotide activation of a new DNA-dependent polyadenylic acid synthesizing nuclear enzyme. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 11(1), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-291x(63)90024-x

- Imai, S., Armstrong, C. M., Kaeberlein, M., & Guarente, L. (2000). Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature, 403(6771), 795–800. https://doi.org/10.1038/35001622

- Bieganowski, P., & Brenner, C. (2004). Discoveries of Nicotinamide Riboside as a Nutrient and Conserved NRK Genes Establish a Preiss-Handler Independent Route to NAD+ in Fungi and Humans. Cell, 117(4), 495–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00416-7

- Belenky, P., Racette, F. G., Bogan, K. L., McClure, J. M., Smith, J. S., & Brenner, C. (2007). Nicotinamide Riboside Promotes Sir2 Silencing and Extends Lifespan via Nrk and Urh1/Pnp1/Meu1 Pathways to NAD+. Cell, 129(3), 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.024

- Massudi, H., Grant, R., Braidy, N., Guest, J., Farnsworth, B., & Guillemin, G. J. (2012). Age-Associated Changes In Oxidative Stress and NAD+ Metabolism In Human Tissue. PLoS ONE, 7(7), e42357. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042357

- Brakedal, B., Dölle, C., Riemer, F., Ma, Y., Nido, G. S., Skeie, G. O., Craven, A. R., Schwarzlmüller, T., Brekke, N., Diab, J., Sverkeli, L., Skjeie, V., Varhaug, K., Tysnes, O.-B., Peng, S., Haugarvoll, K., Ziegler, M., Grüner, R., Eidelberg, D., & Tzoulis, C. (2022). The NADPARK study: A randomized phase I trial of nicotinamide riboside supplementation in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Metabolism, 34(3), 396-407.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2022.02.001

- Vreones, M., Mustapic, M., Moaddel, R., Pucha, K. A., Lovett, J., Seals, D. R., Kapogiannis, D., & Martens, C. R. (2022). Oral nicotinamide riboside raises NAD+ and lowers biomarkers of neurodegenerative pathology in plasma extracellular vesicles enriched for neuronal origin. Aging Cell, 22(1), e13754. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13754

- Bandi, V. K., Chundru, V. K., Yarasani, A., Gajula, R., Pulipaka, V. K., & Syed, T. (2025). Comparative efficacy of a standardized herbal composition LN22199, nicotinamide riboside, and their combination on NAD+ metabolism in healthy aging adults. Journal of Functional Foods, 135, 107115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2025.107115

- Zhou, B., Wang, D. D., Qiu, Y., Airhart, S., Liu, Y., Stempien-Otero, A., O’Brien, K. D., & Tian., R. (2020). Boosting NAD Level Suppresses Inflammatory Activation of PBMC in Heart Failure. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 130(11), 6054–6063. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci138538